The Unbroken Line: From Reconstruction Denied to Resistance Reborn

A History of Supremacy and the Struggle Against It

Open PDF in New Tab

View The Unbroken Line (PDF)

Abstract

This dissertation interrogates the persistent and evolving structures of white supremacy in the United States, tracing a continuous thread from the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the subsequent collapse of Reconstruction to the resurgent forms of racism, xenophobia, and authoritarianism in the twenty-first century. It contends that white male Christian supremacy is not a Southern aberration or relic of a distant past, but a constitutive, adaptive feature of American law, politics, culture, and identity—sustained by intersecting systems of state violence, exclusionary policy, economic exploitation, and enduring national mythologies.

Rejecting narratives of linear racial progress, this study examines the mechanisms through which supremacist power has survived and transformed: from the restoration of Confederate power and the institutionalization of the Ku Klux Klan during the so-called Redemption, through the entrenchment of Jim Crow and nationwide practices of redlining, eugenics, and exclusionary immigration law. The project traces how American innovations in racial ideology and law were exported and adapted by fascist regimes abroad, most notably in Nazi Germany’s appropriation of U.S. eugenics and segregation statutes. Contemporary echoes of this unbroken line are analyzed through the rise of the carceral state, the backlash politics of the Southern Strategy, and the open resurgence of white nationalism and evangelical authoritarianism in the era of Trump.

In parallel, this dissertation foregrounds the rich and multifaceted history of resistance—arguing that the struggle against oppression has been equally unbroken. It follows the arc of resistance from radical abolitionists, Black Reconstructionists, and Indigenous activists to twentieth-century formations such as the Black Panther Party, the American Indian Movement, labor unions, and feminist and queer liberation groups. Contemporary movements, from Standing Rock water protectors to Black Lives Matter, youth climate strikes, and intersectional coalitions, are situated within a tradition of radical imagination and mutual aid, continually re-envisioning freedom and solidarity in response to new forms of domination.

Methodologically, the work synthesizes congressional debates, Supreme Court opinions, presidential memos, FBI and COINTELPRO files, oral histories, trial transcripts, media coverage, and contemporary polling data, as well as a broad array of recent scholarship in history, critical race theory, gender studies, and political science. The dissertation’s approach is interdisciplinary, weaving legal analysis with archival research and close readings of activist texts and speeches. It also incorporates visual, oral, and digital evidence to capture the embodied and performative aspects of resistance.

The central argument is that the “unfinished revolution” of American democracy cannot be understood apart from the mutually constitutive dynamics of supremacy and resistance. Lasting transformation requires confronting the structural and cultural underpinnings of exclusion—dismantling not only explicit forms of racial and gendered violence but the everyday practices of complicity and complacency that sustain them. In charting both the brutality and creativity of this history, the dissertation calls for a politics of memory, radical imagination, and collective courage. It challenges both scholars and activists to recognize that the struggle for justice is not a closed chapter, but a living, revolutionary task that demands vigilance and hope.

Introduction: The Phantom Limb of Justice

Frederick Douglass’s enduring maxim— “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” Frederick Douglass, “West India Emancipation,” Speech, Canandaigua, NY, August 3, 1857, in The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, Vol. 3 (1855–63), ed. John W. Blassingame (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 204. —rings as a warning and a summons across the long arc of American history. This principle is not merely rhetorical; it is the hard-won lesson of every emancipatory struggle, every moment when marginalized people have challenged entrenched power. Yet, just as power’s grip is unyielding, so too is its capacity for regeneration. The American experiment, heralded for its founding aspirations of liberty and equality, has been just as consistently marked by cycles of liberation and backlash, progress and retrenchment, promise and betrayal.

Nowhere is this dialectic more painfully crystallized than in the events surrounding the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. That act did not merely extinguish the life of a president—it snuffed out the fragile, flickering promise of a radical Reconstruction. The nation stood, briefly, at a crossroads where the machinery of slavery had been shattered by war, and the prospect of an interracial democracy, built on the ruins of the Confederacy, appeared within reach. As historian Eric Foner argues, Lincoln’s death “removed the one figure with both the will and the power to forge a genuinely new order in the South.” Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 521. In his absence, the federal government’s resolve faltered, the tides of white supremacy surged back, and the “unfinished revolution” of Reconstruction gave way to a restoration of racial hierarchy under new guises.

The “phantom limb” of justice—a phrase that evokes both the lingering sensation of what once was, and the pain of what has been violently severed—thus becomes a guiding metaphor for the post-Civil War United States. The aspirations of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, of Black suffrage, land redistribution, and equal protection, were felt but not fully realized; they became memories of a body politic that might have been, but was systematically mutilated by violence, law, and myth. The recurring return to this missing justice is evident in every subsequent generation’s struggle, and in the continuous thread of trauma and resistance that runs from emancipation to the present day.

This dissertation contends that the collapse of Reconstruction was not a tragic historical detour, nor merely a Southern failure. Rather, it marked the consolidation of a deliberate, adaptive, and ultimately national system of white, male, Christian supremacy. This “unbroken line” weaves through the story of Redemption governments and Black Codes, but also through the Chinese Exclusion Act, the dispossession and forced assimilation of Indigenous nations, the eugenics movement and its export abroad, Jim Crow apartheid, New Deal redlining, McCarthyism, and the modern era’s carceral state and militarized policing. This line is neither linear nor inevitable; it is, as Douglass and later Angela Davis have insisted, met at every turn by new forms of organized resistance—abolitionist, labor, feminist, Indigenous, queer, anti-fascist, environmental—that have insisted on the unfinished business of emancipation.

To trace this unbroken line is not merely an act of historical accounting, but a moral and political imperative. By illuminating the through-line that connects the assassination of Lincoln and the failure of Reconstruction to present-day manifestations of authoritarianism, racism, xenophobia, and gendered violence, this work aims to clarify the structures that sustain oppression and the strategies by which it has been, and must be, opposed. It is an inquiry not only into the genealogy of American white supremacy, but also into the persistence and creativity of resistance—how every reassertion of dominance has generated, sometimes in unexpected places, new forms of defiance, coalition, and radical imagination.

Thus, the American revolution, in this telling, is incomplete. Its promises remain both vital and violated, its struggles unfinished. The phantom limb of justice—felt, mourned, but not restored—haunts every movement for freedom in this nation. But it also beckons, reminding us that what was lost can, through collective courage and memory, be fought for again.

Chapter 1: Reconstruction Betrayed

1.1 Presidential Retreat and the Return of Confederate Power

The years immediately following the Civil War witnessed not only the promise of national rebirth but also the astonishing resilience and speed with which the prewar social order reasserted itself in the American South. Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, just days after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, marked the transition from a radical—if fragile—moment of transformation to an era characterized by reaction and betrayal. As historian Eric Foner has noted, “Lincoln’s death changed the entire balance of political forces. What might have been a thoroughgoing revolution in Southern society quickly became a restoration of much that had gone before.” [1]Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 181.

Andrew Johnson, a Southern Democrat and former slaveholder from Tennessee, ascended to the presidency with a set of attitudes and priorities strikingly different from his predecessor. While Johnson’s early rhetoric hinted at harsh treatment for Confederate leaders, his policies soon revealed both leniency and a personal animus toward both Black Americans and the so-called “Radical Republicans.” In the spring and summer of 1865, Johnson issued a sweeping series of presidential pardons: “every Confederate who pledged loyalty to the Union (with a few exceptions) could regain his rights and property.” [2]Hans L. Trefousse, Andrew Johnson: A Biography (New York: W.W. Norton, 1989), 293–305. In a matter of months, more than 13,000 pardons were granted to prominent Confederates, including former Vice President Alexander Stephens and a host of Southern governors and military officers. [3]Ibid.; Foner, Reconstruction, 184–186.

The immediate effect was the restoration of Southern elites to political and economic power. “The old leaders are back in office, the old doctrines back in force, and the old antagonism toward the government of the Union is scarcely veiled,” warned the Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction in 1866. [4]Report of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction, 1866, 39th Congress, 1st session, House Report No. 30, Part IV, 6. State legislatures in the former Confederacy, convening under Johnson’s lenient terms, re-elected many of the same men who had led the secessionist cause. In Georgia, for example, the first postwar legislature included six former Confederate generals and over two dozen colonels and majors; in Alabama, the postwar governor was himself a former general. [5]Foner, Reconstruction, 185.

This rapid re-empowerment of the planter class and political elite was not merely symbolic. As historian Leon Litwack notes, “It was almost as if the war had not been fought. In courthouse and statehouse, in plantations and towns, the old order reasserted itself with stunning speed.” [6]Leon F. Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Knopf, 1998), 65. The restoration was codified in a host of “Black Codes”—laws drafted and enacted throughout the South with the clear intention of circumscribing Black freedom as tightly as possible. Mississippi’s Black Code of 1865, for example, declared that “No negro or freedman shall be permitted to rent or keep a house within any town or city…unless by special permission of the board of police,” and that “all freedmen, free negroes and mulattoes…found on the second Monday in January, 1866, or thereafter, with no lawful employment or business, or found unlawfully assembling themselves, shall be deemed vagrants.” [7]Laws of Mississippi, 1865, ch. 6, sec. 1–4, in Reconstruction: The Official Documents, ed. Walter L. Fleming (Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark, 1906), 64–65.

Governor Benjamin Humphreys of Mississippi stated the intent of these codes with chilling clarity, declaring that their purpose was to make the status of Black Americans “as near to slavery as possible.” [8]C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955), 33. These codes were enforced by all-white police forces, former Confederate soldiers now remobilized under new banners. Violence, intimidation, and forced labor contracts replaced the whips and chains of chattel slavery.

Reports from the Freedmen’s Bureau—established by Congress in March 1865 to assist and protect newly freed Black Americans—document “hundreds of cases of whippings, forced labor contracts, and lynching” in states like Mississippi and Louisiana within the very first year after Appomattox. [9]Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, National Archives, microfilm publication M752, roll 18. Bureau agents in Vicksburg wrote of “ex-Confederate officers resuming their old positions as if the war had not occurred, compelling freedmen to sign contracts under duress and punishing those who refused with violence or expulsion.” [10]Ibid.; Foner, Reconstruction, 199.

This restoration was not isolated to a few states or counties, but was a coordinated campaign to reconstitute white rule and subvert the meaning of emancipation. General Carl Schurz, dispatched by President Johnson to investigate Southern conditions, reported back to Washington in 1865: “The great mass of the Southern people are honestly and earnestly opposed to the elevation of the Negro to the plane of the white man, socially and politically…They accept the result of the war only so far as compelled by necessity.” [11]Carl Schurz, Report on the Condition of the South (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1865), 40.

Thus, the opening years of Presidential Reconstruction were less a transition to freedom than a rebranding of old hierarchies. Through the intertwined mechanisms of law, violence, and federal complicity, the South succeeded in restoring much of its antebellum order—an order now shorn of legal slavery but still animated by white supremacy. The betrayal of Black freedom and the restoration of Confederate power set the stage for the next century’s struggle—a struggle that would demand new forms of resistance and, as yet, remains unresolved.

1.2 Klan Terror and the Myth of the “Lost Cause”

The collapse of Presidential Reconstruction not only restored white elites to power in government but unleashed a wave of terror designed to enforce the boundaries of the new racial order. In the winter of 1865–66, a secretive brotherhood took shape in the ruins of the Confederacy. The Ku Klux Klan, founded by six former Confederate officers in Pulaski, Tennessee, quickly evolved from a “social club” into a paramilitary engine of counterrevolution, determined to reestablish white supremacy through violence, fear, and spectacle. [1]David M. Chalmers, Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan (Durham: Duke University Press, 1981), 10–16.

By 1868, the Klan had established chapters in nearly every Southern state, with membership estimated in the tens of thousands. Armed and often masked, Klan riders conducted nighttime raids, targeting Black families, schools, churches, and Republican political meetings. Their tactics—whippings, mutilations, rapes, arson, and murder—were explicitly intended to terrorize both newly enfranchised Black citizens and their white allies. As the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States (the “Klan Hearings”) recorded in 1871, the Klan’s objectives were nakedly political: to “destroy the power of the ballot in the hands of Black men, and to punish those whites who supported them.” [2]Report of the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States (Ku Klux Klan Hearings), 42nd Congress, 2nd session, 1872, 53–65.

Testimonies from the hearings are harrowing. “They told me they would kill me if I voted Republican,” recounted a Black witness from Alabama. Another described the torture of local teachers who dared instruct Black children: “They whipped her until the blood ran in streams and said she was educating the n——s above their place.”[3]Ibid., testimony of Peter Crosby, Alabama, 1871. Klan leaders and sympathizers, when called before Congress, sometimes openly confessed to organizing “regulators” to discipline “uppity” freedmen. One former Klan member admitted, “We made it our business to put them in their place by any means necessary.”[4]Ibid., testimony of John W. Morton, Tennessee, 1871.

A crucial aspect of the Klan’s effectiveness was its close relationship with local authorities. In many towns, sheriffs, judges, and even mayors were either sympathetic to, members of, or actively complicit with the Klan’s activities. Reports to the Freedmen’s Bureau and Congressional investigators noted, “The distinction between police and Klansman is often nonexistent; the same man serves both roles, donning the mask at night and the badge by day.”[5]Records of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, National Archives, M752, roll 21; Foner, Reconstruction, 428–431. This deliberate blurring of legal and extralegal violence created an environment in which Black people, and white Republicans, could find no sanctuary—not even from the state itself.

The Klan’s reign of terror played a central role in undermining Reconstruction democracy. In the elections of 1868 and 1870, widespread threats and violence suppressed Black turnout and drove Republican officials from office. Historian Eric Foner argues, “Wherever the Klan flourished, Black political participation plummeted, and white Democratic control was restored.”[6]Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 425–435. The “Redemption” of Southern governments, as white elites called it, was achieved through systematic intimidation and bloodshed.

While the Klan’s initial reign waned after federal intervention—including the Enforcement Acts of 1870–71 and the brief presence of federal troops—its legacy endured. The template of masked, organized racial violence would be revived in subsequent generations, not only by later incarnations of the Klan but by a wider culture of lynching and white terror throughout the Jim Crow era.

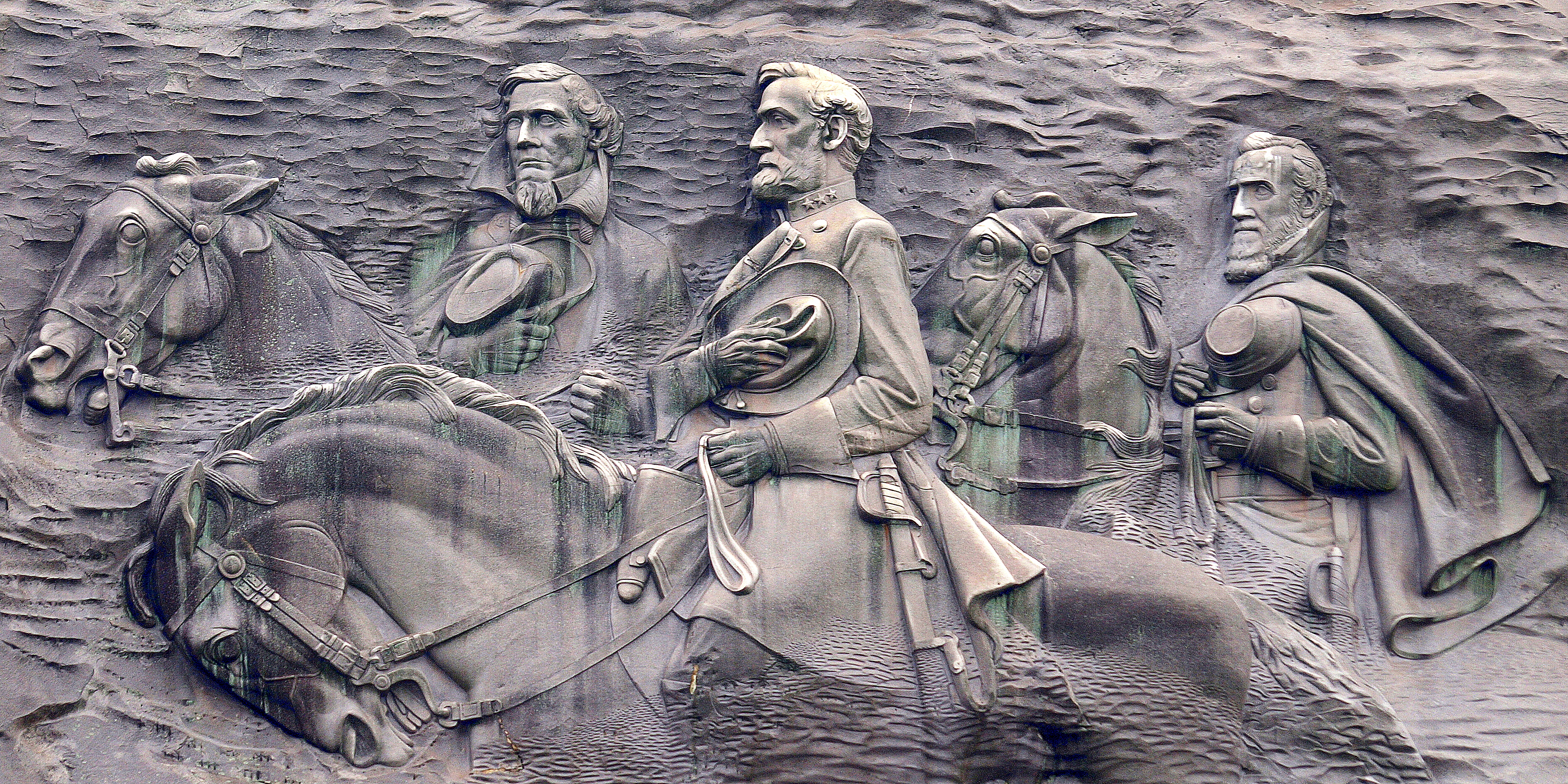

Parallel to this campaign of violence, white Southerners waged a cultural and ideological war to recast the Civil War and Reconstruction. The “Lost Cause” mythology emerged in the late nineteenth century as a deliberate effort to rehabilitate the Confederacy, romanticize its leaders, and recenter white suffering as the true tragedy of the war. Organizations such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), along with veterans’ groups and Southern politicians, orchestrated an extensive project of public memory. Caroline Janney’s research documents how, between 1890 and 1920, over 700 Confederate monuments were erected across Southern towns, each serving as “a tool of terror and instruction, a public assertion of who controlled space, memory, and power.”[7]Caroline E. Janney, Remembering the Civil War: Reunion and the Limits of Reconciliation (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 164–180.

The UDC and their allies rewrote textbooks, lobbied for Confederate Memorial Days, and installed monuments not just in cemeteries but at courthouses, town squares, and schools. These physical markers were not mere relics or neutral tributes to the dead. As legal scholar Michelle Alexander notes, “Monuments were raised not at the time of the war, but at the moment when Black advancement was most threatening to the established order—when Jim Crow was being consolidated and Black political agency had to be symbolically and physically erased.”[8]Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2010), 36.

Thus, the “Lost Cause” mythology and Klan terror worked in tandem. The first, through violence and spectacle, enforced the boundaries of white supremacy in daily life; the second, through memory and myth, justified and sanctified that violence, embedding it within the landscape and psyche of the region. This intertwined legacy ensured that Reconstruction’s fleeting experiments in democracy and racial justice would be remembered not as a moment of hope, but as an aberration, violently corrected and ritually mourned by a culture determined never to let it return.

1.3 Northern Complicity and the Compromise of 1877

The end of Reconstruction was not simply the outcome of Southern intransigence or the exhaustion of idealism in the South; it was also the result of calculated, persistent complicity among Northern elites, politicians, and the business class. For more than a century, historians have debated the motivations that underpinned the North’s retreat: Was it racism, economic calculation, or political exhaustion that proved decisive? Modern scholarship and a rich trove of congressional records, personal correspondence, and press coverage make clear that it was all three—often working in concert to eclipse the goals of Black freedom and multiracial democracy. [10]Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 571–602.

In the immediate postwar years, the North’s commitment to Reconstruction was never unqualified. While abolitionists, Radical Republicans, and some veterans supported robust federal intervention to remake Southern society, they were counterbalanced by moderates and conservatives who saw rapid sectional reconciliation as the ultimate goal. As Leon Litwack observed, “For the North, reunion took precedence over justice; the nation’s business class and politicians saw more profit in reconciliation with Southern whites than in the unfinished revolution of Black freedom.” [11]Leon F. Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Knopf, 1998), 65. The pressures to restore order, reopen Southern markets, and resume profitable trade quickly eclipsed the promises made to formerly enslaved people.

Political calculations also played a central role. The 1870s were years of economic upheaval: the Panic of 1873, followed by a protracted depression, devastated industries and left millions unemployed. As white working-class discontent grew, Northern politicians—including President Ulysses S. Grant—faced mounting pressure to focus on economic recovery and to quell labor unrest rather than enforce Reconstruction in the South. At the same time, racist stereotypes about “Black incapacity” and “corrupt Republican governments” were stoked by both Democratic and Republican newspapers, undermining Northern public support for federal intervention. The “weariness” that Eric Foner and others have chronicled was thus shaped as much by propaganda and prejudice as by any natural fatigue. [10]Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), 571–602.

These trends converged in the tumultuous presidential election of 1876, a contest marked by fraud, intimidation, and a contested result in several Southern states. Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel J. Tilden each claimed victory. The crisis was resolved only through backroom negotiation—what came to be known as the Compromise of 1877. In exchange for conceding the presidency to Hayes, Republicans agreed to withdraw the remaining federal troops from South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana, effectively ending any hope of further federal protection for Black civil rights or for Republican state governments in the South.

The consequences were immediate and devastating. With federal troops gone, “Redeemer” governments—white Democrats dedicated to restoring prewar hierarchies—seized power throughout the region. Within months, Southern legislatures and constitutional conventions enacted a wave of new laws and constitutions that nullified Reconstruction’s gains. Black suffrage was curtailed through poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses; integrated schools and public accommodations were dismantled; and a new system of convict leasing and racialized violence took root, laying the foundation for what Douglas Blackmon has described as “slavery by another name.” [12]Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (New York: Anchor, 2008), 54–70.

The collapse of Reconstruction was not simply a “tragic accident” or the result of Southern resistance alone, but an active process of national abandonment. Northern editorial boards praised the “return of order,” Wall Street cheered the “stability” of Southern markets, and Congress turned its attention to westward expansion, industrialization, and empire. As W.E.B. Du Bois would later write, “The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.” [13]W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880 (New York: Free Press, 1998 [1935]), 30.

This era of retreat and complicity not only allowed white supremacy to reassert itself in the South but also set enduring precedents for the limits of American democracy. It revealed the fragility of interracial political coalitions, the ease with which economic and racial interests could override justice, and the willingness of national institutions to sacrifice Black rights on the altar of reunion. The legacy of the Compromise of 1877 is thus not merely historical: it is a recurring feature in the American story, echoing in later eras whenever the pursuit of justice has been deemed too costly or inconvenient for those in power.

Chapter 2: Systemic Racism and Supremacy Beyond the South

2.1 The Chinese Exclusion Act and Racial Nativism

The notion that racism in America was a regional phenomenon, confined to the Jim Crow South, collapses under the weight of both documentary evidence and lived experience. Indeed, some of the most sweeping—and enduring—systems of racial exclusion originated in the so-called “free” North and West, manifesting in federal law, popular culture, and everyday practice.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first major law in American history to single out an entire group for exclusion based explicitly on race and nationality. Its passage was the culmination of decades of agitation, violence, and legal maneuvering aimed at Chinese immigrants, who had begun arriving on the West Coast in large numbers during the Gold Rush and the construction of the transcontinental railroad. As historian Erika Lee observes, “Chinese exclusion was not just a response to economic competition, but an articulation of a larger white supremacist vision—one that imagined the United States as a fundamentally white nation.” [1]Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 7–9.

By the 1870s, anti-Chinese sentiment had become a political staple in California and the Pacific Northwest, frequently resulting in mob violence and deadly expulsions. In 1871, a white mob in Los Angeles lynched 19 Chinese men and boys; in the 1885 Rock Springs massacre, vigilantes killed at least 28 Chinese miners and expelled hundreds more from Wyoming Territory. State and local governments passed a patchwork of “foreign miner” taxes, discriminatory licensing laws, and segregated schools, but it was the federal government that would ultimately sanctify this racism in law. [2]Jean Pfaelzer, Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans (New York: Random House, 2007), 72–91.

The Chinese Exclusion Act, passed by overwhelming margins in both the House and Senate, was explicit in its intent and scope. Section 1 declared, “the coming of Chinese laborers to the United States…is hereby suspended.” [3]U.S. Congress, Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, 47th Congress, 1st session, Chapter 126. The law barred Chinese laborers—though not merchants, diplomats, or students—from entry for ten years, renewed repeatedly and made permanent in 1902. Most Chinese already in the United States could not naturalize, and reentry after any trip abroad became nearly impossible, dividing families for generations.

Debate in Congress made the racial animus underlying the act unmistakable. Senator John F. Miller of California declared during debate, “Chinese are not and cannot become Americans. They are a race apart, and their presence threatens the purity of our institutions and our blood.” [4]Congressional Record, 47th Congress, 1st session, April 17, 1882, 1631. Newspapers across the North, such as the New York Times and Harper’s Weekly, published lurid illustrations of “Yellow Peril” and endorsed exclusion as a national imperative.

Legal challenges to the Act did not find sympathy in the courts. In Chae Chan Ping v. United States (1889), the Supreme Court—by unanimous decision—upheld the federal government’s “plenary power” to exclude aliens as an extension of national sovereignty. The Court’s opinion warned of the “danger to our institutions posed by an alien race,” rationalizing that “the presence of foreigners of a different race, in this instance from the East, who will not assimilate with us…may be injurious to the public interest.” [5]Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889). The ruling not only confirmed the legitimacy of Chinese exclusion, but also established a legal framework later used to justify bans on Japanese, South Asians, and other groups deemed “unassimilable.”

The legacy of the Chinese Exclusion Act is vast and chilling. It inaugurated a new era in U.S. immigration policy, shifting the legal presumption from one of openness to one of selective, racialized restriction. By 1924, Congress extended similar exclusions to nearly all Asians, imposed national origins quotas to “preserve the ideal of American homogeneity,” and cemented the logic of whiteness as a precondition for belonging. [6]Mae Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 18–45. As Mae Ngai has shown, the category of the “illegal alien” itself is a creation of this period—a product of laws designed to criminalize racialized outsiders and regulate the borders of American identity. [7]Ibid., 4–7.

This era of exclusion demonstrates that systemic racism and white supremacy have always been national, not sectional, projects. They have shaped not only Southern institutions, but the very structure of American law, citizenship, and memory, defining the “us” of the United States as white, Christian, and native-born—while relegating others, from the Chinese laborer to the present-day asylum seeker, to perpetual foreignness and suspicion.

2.2 Native American Boarding Schools and Forced Assimilation

The drive to eliminate Indigenous autonomy and identity was not confined to war or dispossession of land; it persisted—arguably intensified—after the Civil War through a set of cultural policies intent on what policymakers called “assimilation.” By the late nineteenth century, the United States government had shifted its “Indian problem” from open warfare to a systematic effort to dismantle Native nations from within, targeting the youngest and most vulnerable through the boarding school system.

Central to this new campaign was the principle articulated by Captain Richard Henry Pratt, a veteran of the Indian Wars and the founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. In his now infamous 1892 speech, Pratt set forth the policy’s animating logic: “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one… In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” [1]Richard Henry Pratt, “The Advantages of Mingling Indians with Whites,” speech, 1892, Proceedings of the National Conference of Charities and Correction, 46. Pratt’s words were not metaphorical; they became the basis for federal Indian policy for nearly a century.

The Carlisle School, established in 1879, was the prototype for over 350 similar institutions nationwide. Native children—some as young as four or five—were forcibly removed from their homes and transported hundreds or even thousands of miles away. Upon arrival, they underwent immediate and traumatic “civilization” rituals: their hair, considered sacred in many Indigenous cultures, was cut; their traditional clothing replaced with military uniforms; and their names Anglicized or replaced with numbers. [2]Carlisle Indian Industrial School Digital Resource Center, Dickinson College Archives, http://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/. Children caught speaking their languages or practicing ceremonies faced beatings, solitary confinement, or deprivation of food and water. [3]Brenda J. Child, Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900–1940 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 33–40. Many students described the experience as one of profound loss and alienation—one survivor later recalled, “I lost my language. I lost my family. I lost who I was.” [4]Quoted in Jacqueline Fear-Segal, White Man’s Club: Schools, Race, and the Struggle of Indian Acculturation (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 141.

Boarding schools were not merely sites of cultural erasure; they were also loci of physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. Recent research, enabled by the opening of school archives and the testimony of survivors, has documented rampant malnutrition, infectious disease, forced labor, and frequent deaths—often from tuberculosis or influenza, but also from neglect and violence. [5]Margaret D. Jacobs, A Generation Removed: The Fostering and Adoption of Indigenous Children in the Postwar World (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 54–82. Carlisle alone recorded nearly 200 child deaths in its cemetery, but the true toll is incalculable, as many bodies were returned home without records or buried anonymously on school grounds. [6]Carlisle Indian School Project, “Burial Records,” Dickinson College. The federal government, church authorities, and school administrators often ignored or actively concealed evidence of mistreatment.

The curriculum at Carlisle and other boarding schools focused primarily on industrial and domestic labor, reflecting the belief that Indigenous people should be trained for subservient roles within white society. Boys were taught agriculture and manual trades; girls, sewing and domestic service. This vocational training was paired with relentless Christianization, enforced through daily chapel and religious instruction. Native spirituality, arts, and governance structures were denigrated as “savage superstitions.” [7]David Wallace Adams, Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1995), 126–149. In short, the schools functioned as laboratories of cultural genocide.

Despite this, resistance persisted. Students staged covert acts of defiance: secretly speaking their languages at night, running away to return to their families, or sabotaging school routines. At Carlisle, one of the most famous acts of resistance was the 1892 “Great Escape,” when a group of students fled, walking hundreds of miles home before being captured and returned. [8]Adams, Education for Extinction, 210–211. Oral histories and recent commissions, such as the 2021 U.S. Department of the Interior Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, have revealed the scope and trauma of these institutions and the resilience of Indigenous families who survived them. [9]U.S. Department of the Interior, “Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report,” May 2022.

The boarding school era has left a complex and ongoing legacy. While some former students speak of valuable friendships or skills acquired, the dominant narrative—reflected in countless testimonies and growing scholarship—is one of rupture, generational trauma, and cultural loss. As historian Margaret Jacobs writes, “Federal Indian boarding schools were key sites of colonial violence—spaces where Native identities were targeted for eradication, but also where Native peoples resisted, survived, and remembered.” [10]Margaret D. Jacobs, “Remembering the Forgotten Children: The U.S. Federal Indian Boarding School System,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 15, no. 2 (2016): 186.

This story is not simply one of the past. The forced assimilation of Indigenous youth—its methods, traumas, and rationalizations—echoes today in foster care systems, struggles for language revitalization, and calls for truth and reconciliation. The reckoning with this history, still unfolding, challenges Americans to confront not only what was done in the name of civilization, but what survival and justice might yet demand.

2.3 The Spread of Jim Crow and Segregation

The narrative that Jim Crow segregation and racial violence were Southern problems, while the North embodied the ideals of freedom and equality, has been repeatedly challenged by both scholarship and lived experience. In truth, the “color line” was drawn—and enforced—across the entire country, often with innovative brutality and systemic reach.

The Great Migration, beginning around 1915, saw millions of African Americans flee the terrorism of the South—lynching, peonage, and political disfranchisement—for the promise of safety and opportunity in northern and western cities. Yet as Isabel Wilkerson and others have documented, the North was hardly a promised land. [1]Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010), 82–89. Instead, Black migrants found “new forms of exclusion dressed in the clothing of modernity and progress.” [2]Ibid., 103.

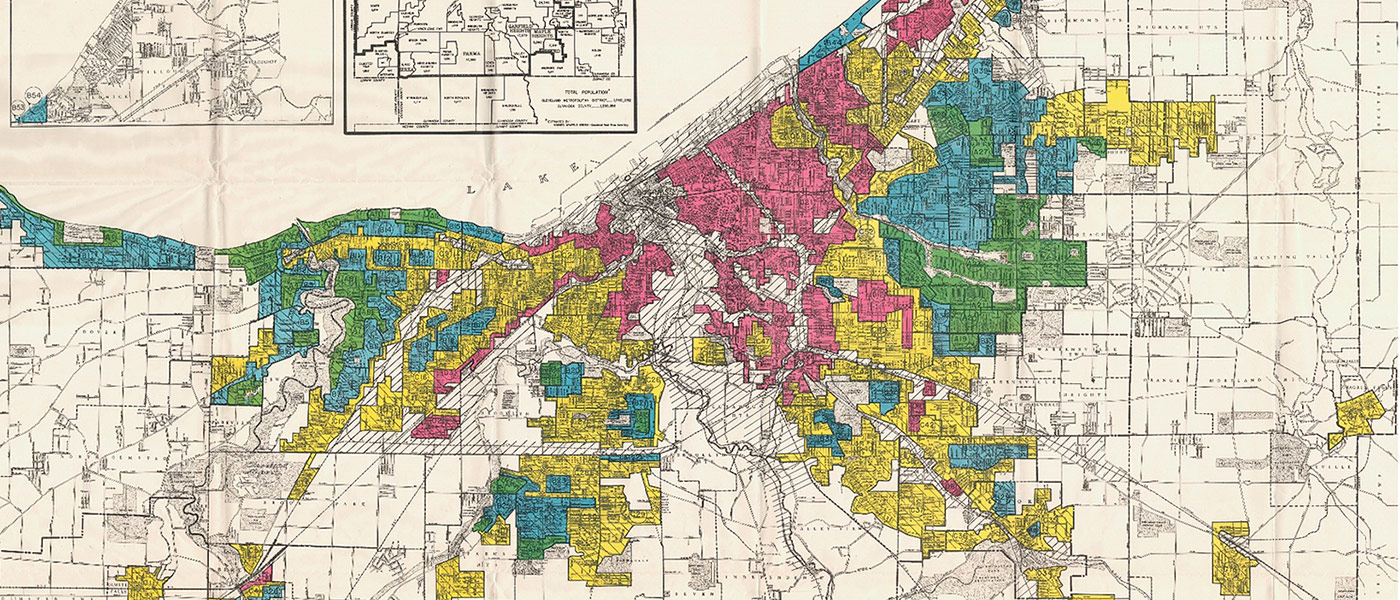

In the urban North, the principal instrument of racial segregation became the real estate market, with federal sanction and local complicity. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), created during the New Deal to stabilize the housing market, introduced “residential security maps” that categorized neighborhoods by perceived investment risk. These maps, now digitized by the Mapping Inequality project, used red ink to outline neighborhoods with Black or other minority populations, labeling them “hazardous” or “definitely declining.” The presence of “Negro infiltration” was considered a primary indicator of financial risk. [3]Mapping Inequality Project, University of Richmond, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/. The language of these appraisals is unambiguous: “If Negroes continue to buy property in this neighborhood, values will decrease and it will become increasingly difficult to sell or rent to white families.” [4]HOLC Appraisal for Cleveland, Ohio, Area D6, 1937, quoted in Rothstein, The Color of Law, 64.

The effect of redlining was to systematically deny home loans, insurance, and investment to Black neighborhoods, locking millions of African Americans out of the postwar boom in homeownership and intergenerational wealth. By 1940, as Richard Rothstein notes, “98% of federally insured loans went to white Americans.” [5]Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017), 64. This denial of capital did not merely reflect racist attitudes; it produced durable material inequalities, undergirding school segregation, business disinvestment, and cycles of poverty that persist to this day.

Racism in the North was enforced not just through policy, but also through organized violence and exclusionary labor practices. Labor unions, particularly the powerful American Federation of Labor (AFL), often codified racial exclusion. AFL membership rolls and convention minutes from the early 20th century show explicit bans on Black, Asian, and Latino workers in dozens of skilled trades and industries. When Black workers did break into unionized fields—often during strikes or labor shortages—they were frequently subjected to harassment, assault, and expulsion once white workers regained leverage. [6]Philip S. Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619–1981 (New York: International Publishers, 1981), 124–157. In some cases, unions established separate, segregated locals or “auxiliaries” for Black members, offering inferior benefits and limited bargaining power. [7]Ibid.; Melvin Oliver and Thomas Shapiro, Black Wealth/White Wealth (New York: Routledge, 1995), 74–77.

Beyond the workplace and the real estate market, the North also developed its own methods of direct, public racial exclusion. “Sundown towns”—municipalities that excluded Black people and other minorities after dark, often through the threat or use of violence—proliferated across Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, California, and beyond. Historian James Loewen, who catalogued thousands of such towns, uncovered photographic archives of city limit signs reading: “N——, Don’t Let the Sun Set on You Here.” [8]James W. Loewen, Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism (New York: New Press, 2005), 4, 78–112. Oral histories from Black families recount the constant threat of police harassment or mob violence when passing through or attempting to settle in these places. [9]Ibid., 185–210.

Collectively, these systems reveal the deeply national character of racial segregation and violence in America. While the specific mechanisms varied—lynching and legal segregation in the South, redlining and “restrictive covenants” in the North, labor exclusion and sundown towns everywhere—the outcome was a nation partitioned by race, opportunity, and fear. As W.E.B. Du Bois observed in 1903, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” [10]W.E.B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (Chicago: A.C. McClurg, 1903), 1. His insight remains trenchant today, as contemporary debates over mass incarceration, environmental racism, and urban gentrification return us again and again to the unfinished business of justice.

Chapter 3: The Export of American Racism

3.1 Eugenics, Nazi Germany, and Racial Law

The influence of American racism has not been confined within national borders. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the United States became a global pioneer not only in the legal construction of white supremacy, but also in the pseudoscientific ideology of eugenics—a movement dedicated to the “improvement” of the human race through selective breeding, segregation, and forced sterilization. American eugenicists found enthusiastic support among politicians, philanthropists, and academics, from Charles Davenport at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory to Margaret Sanger and leading Ivy League universities.[1]Alexandra Minna Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 7–22; Daniel J. Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985), 97–117.

By the 1920s, more than half of U.S. states had passed laws authorizing the compulsory sterilization of the so-called “feeble-minded,” “unfit,” and “unworthy,” with particular focus on people of color, the disabled, and the poor. Virginia’s 1924 Racial Integrity Act was among the most far-reaching: it prohibited interracial marriage and established a regime of racial “classification” based on the notorious “one drop rule.” That same year, the Virginia Sterilization Act provided for the forced sterilization of those deemed unfit for reproduction—a policy upheld by the Supreme Court in Buck v. Bell (1927). Writing for the majority, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes infamously declared, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”[2]Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927).

The global reverberations of these policies were profound and chilling. As historian Edwin Black documents, American eugenics was avidly read, translated, and debated in Europe—nowhere more so than in Germany, where doctors, legal scholars, and Nazi party officials corresponded directly with their American counterparts. The 1933 German “Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring,” which provided for the mass sterilization of the disabled, was directly modeled on American statutes. In the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial after World War II, Nazi defendants cited California’s sterilization law as precedent for their own actions.[3]Edwin Black, War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 2003), 266–278.

Adolf Hitler’s own writings testify to the inspiration he drew from American racial policy. In Mein Kampf, he praised U.S. immigration laws—especially the Immigration Act of 1924 and its national origins quotas—as “models for preserving racial purity,” observing that “The American Union…categorically refuses the immigration of physically unhealthy elements, and simply excludes the immigration of certain races.”[4]Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (Munich: Franz Eher Nachfolger, 1925), trans. Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1943), 404–405. The U.S. was, in Hitler’s eyes, a pioneer in racial statecraft.

Most disturbing of all, recent scholarship has demonstrated that the architects of the Nazi racial state studied and admired the American South’s system of segregation, disenfranchisement, and anti-miscegenation law. In Hitler’s American Model, legal historian James Q. Whitman marshals extensive archival evidence showing that Nazi lawyers in the early 1930s pored over U.S. Supreme Court opinions, state codes, and law review articles to design the infamous Nuremberg Laws. Particularly instructive was Alabama’s “one drop rule,” which codified any person with any discernible Black ancestry as Black and therefore subject to a panoply of restrictions and prohibitions. Whitman notes that “the United States was the leading racist jurisdiction—so much so that even Nazi lawyers were sometimes embarrassed by the harshness of American race law.”[5]James Q. Whitman, Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), 35–47.

Nor was the American influence limited to law: American eugenicists, through organizations like the Eugenics Record Office and the International Congress of Eugenics, fostered an intellectual and institutional exchange that helped to globalize white supremacist thinking. U.S. immigration policy, anti-miscegenation laws, and the logic of “biological threat” laid both conceptual and administrative foundations for later genocidal projects in Germany and beyond.[6]Stefan Kühl, The Nazi Connection: Eugenics, American Racism, and German National Socialism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 23–49.

The traffic in ideas and policies was not unidirectional: the spectacle of Nazi atrocity would, in time, spark global condemnation and a reappraisal of eugenics in the U.S. itself. But the shadow of American race science—its sterilization laws, its obsession with racial purity, its legal innovations in exclusion and segregation—haunts both the history of Nazism and the continuing architecture of racism worldwide.

3.2 Imperialism, Military Occupation, and Detention

The export of American racism is visible not only in the global diffusion of eugenics and race law, but also in the practices of military occupation and detention that accompanied U.S. imperial expansion at the turn of the twentieth century—and which reverberate into the present. In these contexts, techniques of control, containment, and racialized violence developed in domestic “Indian policy” were redeployed against new colonial subjects, creating a template for modern systems of extrajudicial incarceration and state-sanctioned brutality.

The Philippine-American War (1899–1902) provides a particularly revealing case study. Following the defeat of Spain, the United States annexed the Philippines, facing immediate and determined resistance from Filipino nationalists who had fought for independence. American generals, many of whom had previously served on the Western frontier, drew explicitly from their experiences subjugating Native Americans. General James Franklin Bell, in charge of counterinsurgency in Luzon, boasted of using “zones of concentration”—areas where entire populations were forcibly relocated under military guard—to separate guerrillas from their civilian support base.[1]Brian McAllister Linn, The Philippine War, 1899–1902 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000), 206–217. Bell described these camps in correspondence to President McKinley as “essential to breaking the spirit of resistance,” and noted that “the Indian reservation model has demonstrated its value.”[2]Letter, General James Franklin Bell to President William McKinley, 1901, National Archives, Record Group 94.

Conditions in the concentration camps were appalling: overcrowding, disease, inadequate food, and routine violence led to the deaths of thousands. The U.S. press and some members of Congress compared the camps to those recently used by the Spanish in Cuba—a tactic the U.S. had just denounced as an atrocity. Reports from the Philippine Commission document mortality rates in some camps exceeding 20%, primarily due to cholera and starvation.[3]Report of the Philippine Commission to the President, 1900–1901, U.S. Government Printing Office, 381–405. These policies were accompanied by the systematic use of torture, including the infamous “water cure”—a form of waterboarding—employed by U.S. soldiers to extract information and terrorize suspected insurgents.

These methods of military occupation, collective punishment, and forced relocation did not disappear with the end of formal empire; they became a recurring feature of twentieth-century American counterinsurgency and “homeland security.” In Vietnam, the U.S. implemented the “strategic hamlets” program, forcibly relocating rural populations into fortified villages to isolate the Viet Cong. In Guatemala and El Salvador, American advisors trained local forces in the use of “model villages” and detention centers to control indigenous and peasant populations. In Iraq and Afghanistan, U.S. forces revived mass detention and “cordon and search” tactics, again echoing the reservation and concentration camp models developed decades earlier.[4]Alfred W. McCoy, A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, From the Cold War to the War on Terror (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006), 46–65; Nick Turse, Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2013), 155–184.

Domestically, the United States has continued to use mass detention as a tool of racialized statecraft. From the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II to the detention of Central American and Haitian refugees in the 1980s and 1990s, the architecture of American exclusion has repeatedly targeted those marked as racial or national “others.” Most recently, Congressional hearings and investigative journalism have documented the ongoing crisis at Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facilities along the U.S.-Mexico border. Testimony before the House Committee on Oversight and Reform in 2019 revealed that thousands of children and families—many seeking asylum—were being held in overcrowded, unsanitary cages, denied basic medical care, and subjected to conditions that medical experts described as “tantamount to torture.”[5]U.S. Congress, House Committee on Oversight and Reform, “The Trump Administration’s Child Separation Policy: Substantiated Allegations of Mistreatment,” hearing, July 12, 2019. Witnesses and inspectors reported outbreaks of illness, sexual assault, and psychological trauma resulting from prolonged detention and family separation.[6]Caitlin Dickerson, “Thousands of Immigrant Children Said They Were Sexually Abused in U.S. Detention Centers, Report Says,” New York Times, February 26, 2019.

The persistence of these practices—zones of concentration, strategic hamlets, detention camps, and family separation—testifies to the durability and adaptability of American systems of racial control. What began as domestic policy toward Indigenous nations evolved into the technology of empire, and has returned home in the apparatus of mass incarceration and immigration enforcement. Each iteration refines the techniques of surveillance, containment, and dehumanization, while justifying them with the language of security, progress, or civilization.

As critics and survivors alike have argued, these practices are not aberrations, but expressions of a long genealogy of American racism—one that connects the reservation and the plantation, the camp and the border, the battlefield and the prison cell. The ongoing struggle to expose, resist, and dismantle these systems remains one of the central moral and political challenges of our time.

Chapter 4: Repression of Resistance: State Violence and Assassinations

4.1 COINTELPRO, Black Power, and Political Murder

The promise of the civil rights era—embodied in the mass mobilization, legislative victories, and surge of Black self-determination during the 1950s and 1960s—provoked not only grassroots backlash but also systematic, clandestine state repression. Nowhere is this more visible than in the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Counterintelligence Program, known as COINTELPRO. Established in 1956 to combat Communist influence, the program rapidly expanded its focus to encompass Black liberation movements, antiwar activists, Native American organizations, Puerto Rican nationalists, and the broader New Left.

COINTELPRO’s stated aim, as revealed in declassified FBI memos and directives, was to “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” groups and individuals deemed subversive.[1]Federal Bureau of Investigation, “COINTELPRO: Black Extremist,” 1967–1972 (Declassified Files), FBI Records: The Vault, https://vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro. The scope and scale of these efforts were unprecedented in peacetime. Bureau agents infiltrated organizations such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and most aggressively, the Black Panther Party (BPP). Internal documents boasted of successful efforts to plant informants, provoke internal divisions, and disseminate forged letters to foster distrust and paranoia among activists.[2]Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall, Agents of Repression: The FBI’s Secret Wars Against the Black Panther Party and the American Indian Movement (Boston: South End Press, 1988), 38–63. In one infamous instance, the FBI orchestrated an anonymous campaign to sow discord between Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders, even sending King an anonymous letter urging him to commit suicide, later revealed to have originated from the Bureau’s Atlanta office.[3]Beverly Gage, The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr.: From “Solo” to Memphis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 92–105.

The Black Panther Party was singled out for especially ruthless attention. Founded in Oakland in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the BPP articulated a radical vision of Black autonomy, justice, and self-defense. Its Ten Point Program demanded “land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace,” and backed up rhetoric with grassroots action—free breakfast programs, health clinics, and armed patrols of police violence in Black neighborhoods.[4]Black Panther Party, “What We Want, What We Believe: The Ten-Point Program,” The Black Panther, May 15, 1967. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover labeled the Panthers “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country,” issuing directives for their “neutralization by any means necessary.”[5]J. Edgar Hoover, “Black Extremist,” Memo to Special Agents in Charge, August 25, 1967, FBI Vault.

COINTELPRO tactics included constant surveillance, orchestrated arrests on trumped-up charges, frame-ups, and direct collaboration with local police in raids and assassination plots. The murder of Chicago Panther leader Fred Hampton in 1969 is emblematic. Declassified FBI files and subsequent investigations revealed that agent William O’Neal, working as an informant, provided the Chicago Police with detailed floor plans of Hampton’s apartment. On December 4, 1969, police stormed the residence in a pre-dawn raid, firing nearly 100 shots and killing Hampton as he slept beside his pregnant fiancée. Official reports initially claimed the Panthers fired first, but forensic evidence, witness testimony, and later court findings confirmed the police acted as executioners—with the FBI’s direct assistance.[6]Jeffrey Haas, The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2010), 130–145; “U.S. Jury Finds Police Fired Fatal Shots in Panther Raid,” New York Times, April 24, 1970.

The assassination of Hampton was not an isolated incident but part of a broader campaign of lethal repression against Black Power leaders and organizations. Dozens of Panthers were killed in police raids from Los Angeles to New York; many others were imprisoned for decades on questionable evidence. The FBI’s files are rife with language of war: “We must prevent the rise of a ‘messiah’ who could unify and electrify the militant Black nationalist movement,” one memo warned, explicitly naming King, Malcolm X, and Stokely Carmichael as targets.[7]FBI Memo, March 4, 1968, COINTELPRO–Black Nationalist Hate Groups, FBI Vault.

The criminalization and suppression of the Black Panther Party and its Ten Point Program was mirrored by similar campaigns against the American Indian Movement (AIM), the Puerto Rican Young Lords, and antiwar student groups. FBI and local police sought to equate demands for justice, community self-defense, and anti-imperialist critique with criminal conspiracy or treason, justifying mass arrests, grand jury investigations, and paramilitary tactics.

The legacy of COINTELPRO is enduring and corrosive. As historians such as Elizabeth Hinton and Donna Murch argue, the program not only fractured social movements and led to the deaths and imprisonment of dozens of activists, but also set a precedent for subsequent state surveillance and repression of dissent, from the anti-apartheid and environmental movements to Black Lives Matter.[8]Elizabeth Hinton, America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s (New York: Liveright, 2021), 224–256; Donna Murch, Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 157–181. For many Black communities, the “rule of law” came to signify not protection but organized, officially sanctioned violence—a pattern of policing and political suppression that continues to shape American society.

4.2 The Red Scare, Labor, and Indigenous Dissent

The repression of radical resistance in the United States was neither confined to the Black liberation movements nor restricted to the tactics of COINTELPRO. Rather, it formed part of a much broader—and bipartisan—campaign to delegitimize and destroy leftist, anti-racist, feminist, and Indigenous activism under the banner of anti-communism. The Second Red Scare, peaking in the late 1940s and 1950s, institutionalized paranoia as public policy, with consequences that continue to reverberate across American political life.

The political theater of the Red Scare found its most notorious expression in the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, chaired by Senator Joseph McCarthy. Between 1950 and 1954, McCarthy and his allies interrogated thousands of government employees, union leaders, teachers, and artists, searching for evidence of Communist “subversion.” Full transcripts of these hearings—now digitized and publicly available—reveal the extent to which accusations were often based on hearsay, guilt by association, or mere dissent from the political consensus of Cold War America.[1]U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Government Operations, “Army-McCarthy Hearings,” 1954, National Archives; Ellen Schrecker, Many Are the Crimes: McCarthyism in America (Boston: Little, Brown, 1998), 247–260. Careers and lives were ruined: prominent intellectuals, writers, and performers were blacklisted; university professors were fired for attending left-leaning meetings; union organizers and civil rights advocates lost jobs and faced state surveillance for alleged “un-American activities.”[2]Schrecker, Many Are the Crimes, 354–401; Victor S. Navasky, Naming Names (New York: Viking, 1980), 103–141.

The Red Scare targeted labor movements with particular ferocity. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 required union leaders to sign anti-communist affidavits, effectively criminalizing radical labor organizing and excluding the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) affiliates with significant Black, immigrant, and leftist membership. Many of the most effective unions—those advocating for racial integration, equal pay, and industrial democracy—were decimated by government purges, internal splits, and relentless FBI harassment. These policies helped shift American labor away from a vision of class solidarity and toward business unionism, cementing divisions that would weaken working-class resistance for generations.[3]Philip S. Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619–1981 (New York: International Publishers, 1981), 214–226; Nelson Lichtenstein, State of the Union: A Century of American Labor (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 108–132.

Anti-communist hysteria also intersected with gender and sexuality. Feminists, queer organizers, and women’s rights advocates were routinely branded as “dupes” or “tools” of Moscow, echoing the tactics of the earlier “Lavender Scare” that purged suspected LGBTQ individuals from government service. For women of color and Indigenous women, the risk was multiplied: activism in civil rights or community defense was often pathologized as subversive, criminal, or immoral.[4]David K. Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 79–120.

Indigenous resistance, in particular, faced a multi-pronged assault from federal agencies, law enforcement, and the judiciary. The American Indian Movement (AIM), founded in 1968 to combat police brutality, treaty violations, and the destruction of Indigenous lands, became a primary target for infiltration, surveillance, and prosecution. AIM leaders—such as Dennis Banks, Russell Means, and Leonard Peltier—were placed under near-constant observation. The 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee, in which AIM activists and Oglala Lakota elders demanded enforcement of treaty rights and an end to government corruption, was met with a 71-day siege by federal agents, resulting in deaths, injuries, and a wave of indictments.[5]Paul Chaat Smith and Robert Allen Warrior, Like a Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee (New York: New Press, 1996), 224–266.

Leonard Peltier’s ongoing imprisonment was perhaps the most poignant symbol of the state’s repression of Indigenous dissent. However, in February 2025, President Joe Biden commuted Peltier’s life sentence, and he was released from federal prison after nearly 50 years for the 1975 killings of two FBI agents on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Peltier’s release was celebrated by Indigenous communities and human rights organizations, while some law enforcement officials expressed disappointment. He returned home to the Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota, where he was welcomed by family and supporters.

For more information:

MPR News: Peltier Welcomed Home |

PBS NewsHour: Biden Commutes Peltier |

NPR: Peltier Released

In a stunning development, President Joe Biden commuted Leonard Peltier’s sentence in February 2025, ending his nearly 50-year imprisonment. Peltier was released on February 18, 2025, from a federal prison in Florida and returned to the Turtle Mountain Reservation in North Dakota, where he was welcomed by family, spiritual leaders, and supporters.

Biden’s action—commuting rather than pardoning—reflected the ongoing controversy. While law enforcement groups expressed outrage, Indigenous communities and human rights organizations celebrated what they saw as long-overdue justice. Peltier’s release marks a rare victory in a system known more for punishment than reconciliation.

His homecoming is symbolic: not only of personal survival, but of a broader refusal to let resistance be silenced. Peltier’s decades of incarceration are a reminder of the risks faced by those who confront colonial power. His freedom represents not closure, but a continuation of the struggle.

Sources: MPR News, PBS NewsHour, NPR

4.3 The Legacy of Repression

From the Black Panthers to AIM, from labor radicals to queer organizers, the U.S. state has routinely criminalized dissent—especially when it challenges foundational myths of white supremacy, capitalism, and settler colonialism. COINTELPRO was not an aberration, but a blueprint.

Even today, the surveillance of Black organizers, the suppression of protest, and the demonization of antifascist and environmental movements reveal the persistence of this legacy. Yet alongside this repression stands resistance: resilient, creative, and unrelenting.

The arc of history, as it turns out, does not bend on its own. It is pulled—often at great cost—by those who refuse to be neutralized.

Taken together, the Red Scare, labor repression, and the ongoing criminalization of Indigenous resistance illustrate a persistent pattern: the labeling of dissent as treason, the weaponization of law and bureaucracy against social movements, and the enduring power of the state to silence, imprison, or destroy those who threaten the status quo. The legacies of these campaigns remain visible in the marginalization of radical voices, the weakening of labor, and the unresolved injustices facing Indigenous nations—reminders that the defense of “Americanism” has often been a euphemism for the defense of power itself.

Chapter 5: The Long Culture War — Sexism, Xenophobia, and Queerphobia

5.1 The Lavender Scare and the Policing of Sexuality

The mid-twentieth century “Lavender Scare” stands as one of the most extensive state-driven purges of queer individuals in American history, a campaign as thorough—and in many ways as devastating—as the better-known Red Scare. While anti-communism provided the public rationale for postwar repression, the government’s obsession with policing gender and sexuality became an equally potent engine of exclusion, surveillance, and psychological violence.

The roots of the Lavender Scare stretch back to the confluence of the Second World War’s social dislocations and the Cold War’s ideological rigidity. As the United States government built its security state, it adopted the conviction that “sexual deviance” was a direct threat to national security. Federal officials claimed, often without evidence, that homosexuals were vulnerable to blackmail by foreign powers and lacked the “moral fitness” to serve in sensitive positions.[1]U.S. Department of State, “Personnel Security—Homosexuals,” Memorandum, July 10, 1950, National Archives, RG 59. This anxiety was codified in Executive Order 10450, signed by President Eisenhower in 1953, which explicitly named “sexual perversion” as grounds for exclusion from federal employment.[2]Executive Order 10450, “Security Requirements for Government Employment,” April 27, 1953.

The mechanics of the Lavender Scare were elaborate and ruthless. Declassified State Department memoranda from the 1950s reveal the establishment of special investigative units charged with rooting out suspected homosexuals.[3]Johnson, David K., The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 70–92. Agents conducted surveillance, interrogated employees about their personal lives, and pressured colleagues to inform on one another. Anonymous tips, mere rumor, or “immoral conduct” could trigger an investigation and summary dismissal. The names of the accused—sometimes compiled into long lists—were shared across agencies and with local police, ensuring that blacklisted individuals could not easily find new work.[4]Ibid., 93–117.

The consequences were ruinous. As historian David K. Johnson has documented, “more people lost their jobs for alleged homosexuality than for alleged membership in the Communist Party.”[5]Ibid., 3. From the late 1940s through the 1960s, thousands of men and women were fired, forced to resign, or denied security clearances. For many, the resulting “career death” was accompanied by social ostracism, broken families, and in some tragic cases, suicide. The purges created a culture of constant fear and self-censorship—one in which queer government workers lived double lives, concealed their identities, and avoided political activism, even as they witnessed the rise of other liberation movements.[6]George Chauncey, Why Marriage? The History Shaping Today’s Debate Over Gay Equality (New York: Basic Books, 2004), 83–87.

The Lavender Scare did not merely reflect existing social prejudices; it deepened them, shaping national understandings of queerness as both criminal and subversive. Mainstream media, echoing government rhetoric, depicted homosexuals as sick, dangerous, or inherently disloyal. Films, news stories, and pulp novels trafficked in images of the “deviant infiltrator,” conflating sexuality with espionage and treason. These narratives reinforced the marginalization of LGBTQ people far beyond the federal workforce—impacting hiring, housing, and policing across American society.[7]Naoko Shibusawa, “The Lavender Scare and Empire: Rethinking Cold War Antigay Politics,” Diplomatic History 36, no. 4 (2012): 723–752.

Despite this regime of repression, forms of resistance and solidarity began to emerge. LGBTQ individuals subjected to investigation and dismissal often banded together for mutual support, contributing to the early “homophile” movement of the 1950s. Groups like the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis challenged their exclusion, petitioned for legal reforms, and quietly supported those facing persecution.[8]Marc Stein, Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement (New York: Routledge, 2012), 28–44. The links between the Lavender Scare and broader struggles for civil liberties became clearer in the 1960s, as queer activists joined with Black, feminist, and antiwar movements in contesting the logic of national security repression.

The Lavender Scare’s impact extended well beyond the era of McCarthyism, shaping the politics of sexuality and citizenship into the 1970s and beyond. Only in the wake of Stonewall and the gay liberation movement did the power of the security state begin to recede, though the scars of dismissal, surveillance, and forced secrecy remained. As the government continues to wrestle with issues of LGBTQ inclusion, the legacy of the Lavender Scare reminds us how easily the language of security and morality can become weapons of marginalization.

5.2 Intersectional Feminism and Resistance

The postwar movement for justice and equality in America was never a single-issue struggle. While the battles against white supremacy and heteropatriarchy are often recounted as parallel stories, it was at their intersection that some of the most incisive critiques and innovative forms of resistance emerged. Black feminists in particular—whose experiences could not be neatly categorized by either race or gender alone—developed an analysis and praxis that would profoundly shape both activism and theory in the late twentieth century.

The Combahee River Collective, a Boston-based group of Black lesbian feminists active in the 1970s, stands at the center of this legacy. Named for the 1863 raid led by Harriet Tubman to free enslaved people in South Carolina, the Collective’s work was a radical synthesis of personal experience and collective analysis. In their 1977 “Black Feminist Statement”—one of the most influential documents in feminist and anti-racist history—the group declared:

“We are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking.”[1]Combahee River Collective, “A Black Feminist Statement,” 1977, in Beverly Guy-Sheftall, ed., Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought (New York: New Press, 1995), 232, 234.

This assertion did not arise from academic theory, but from the everyday lives of women who faced discrimination and violence not only as Black people in a racist society, or as women in a sexist one, but as Black women whose realities were consistently marginalized by both mainstream (white) feminism and (male-dominated) Black liberation movements. The members of the Collective—Barbara Smith, Demita Frazier, Beverly Smith, and others—wrote with searing clarity about the limits of “single-issue” politics, insisting that genuine liberation could not be achieved for any group unless it dismantled all forms of oppression at once.

Their analysis, articulated through the phrase “interlocking systems of oppression,” anticipated what would later be called intersectionality—a term coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to describe how race, gender, class, and other identities overlap and compound social disadvantage.[2]Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989, no. 1 (1989): 139–167. Long before this framework gained academic traction, the Combahee River Collective grounded it in grassroots organizing: fighting for affordable housing, reproductive rights, anti-violence initiatives, and solidarity with labor and LGBTQ struggles. Their work included collaborations with working-class women’s groups, health collectives, and anti-rape organizations, building alliances that transcended conventional boundaries.[3]Barbara Smith, “A Press of Our Own: Kitchen Table Press and the Black Feminist Revolution,” Signs 20, no. 4 (1995): 885–897; Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017), 44–53.

Importantly, the Collective also rejected the “hierarchy of oppression” that often plagued progressive movements, wherein participants would debate which form of injustice was “most important.” Instead, they insisted on what Audre Lorde, another towering Black lesbian feminist, called “the simultaneity of oppression.”[4]Audre Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 1984), 114–123. For the Combahee River Collective, fighting racism, sexism, homophobia, and economic exploitation was not a matter of shifting priorities, but of recognizing how these systems sustained each other—and how resistance must be equally holistic.

The impact of the Collective’s analysis has been profound and enduring. Their statement is now widely recognized as a founding text for intersectional feminism, queer of color critique, and Black feminist thought. It has influenced generations of activists and scholars, from the women of color feminist movement in the 1980s to contemporary organizations like Black Lives Matter, whose founding principles echo Combahee’s insistence on “collective liberation” and inclusive, queer-affirming politics.[5]Taylor, How We Get Free, 20–43.

At the same time, the Collective’s example remains a challenge to contemporary movements: a reminder that solidarity is not possible without deep engagement with difference, and that real change requires not only policy reform but the transformation of structures, relationships, and consciousness. The Combahee River Collective’s legacy is thus not only a set of theoretical insights, but a lived model of intersectional organizing—one that remains urgently relevant in the face of ongoing racial, sexual, economic, and gender-based violence.

5.3 Immigration, Exclusion, and the Reinvention of Whiteness

The transformation of American immigration policy in the early twentieth century was not simply a story of border control; it was a deliberate and explicit project of racial engineering. The debates and laws of this period reveal the centrality of race—particularly the flexible, evolving notion of “whiteness”—to the making and maintenance of the American nation-state.

The Immigration Act of 1924, also known as the Johnson-Reed Act, represented a turning point in U.S. history. Congressional debates on the bill were rife with overtly racialized language and eugenic ideology. Senator David Reed of Pennsylvania, one of the law’s architects, bluntly declared during Senate debate that the Act would “preserve the ideal of American homogeneity,” stating, “The racial composition of America at the present time thus is made permanent.”[1]U.S. Congress, Senate, Congressional Record, 68th Congress, 1st session, April 8, 1924, 5915. Proponents warned of the “danger” posed by the influx of Southern and Eastern Europeans, Asians, and others considered biologically and culturally incompatible with the nation’s founding stock. Senator Ellison D. Smith of South Carolina proclaimed, “Thank God we have in America perhaps the only nation which does not draw its population from the worst races of Europe.”[2]Ibid., 5981.